other publications

Images and Propaganda: From the Sacred to the Profane

Toby Clark's Art and Propaganda in the 20th Century assumes that images are able to convey information quickly and evoke deep emotions in their viewers. This power of the image derives from its ability to convey a message all-at-once, as a gestalt or whole chunk of meaning.

Since the earliest pictographs and petroglyhs, rock art has expressed what could not be expressed in language, and often had aspirations to the magical and spiritual. It is our ancient sense that images have power and an ability to etch themselves immediately onto consciousness that give them their iconic weight. Religious icons have, for centuries, been used to convey the spirit of the deity, much like the cave paintings and petroglyphs of preceding cultures. Cultural icons--whether persons or things--are objects of admiration which exert a power of influence over us akin to cave paintings and religious symbolism in their own time.

The way the brain processses images also contributes to their power: we can see, remember, and be moved by an image that we have not really thought about. It can enter into consciousness below our analytical radar--or be moving too quickly--and continue to influence us from our subconsciousness. (This is the theme of David Cronenberg's 1983 film Videodrome.) Conversely, when we do engage consciously with the meaning and composition of an image, we can derive great pleasure from the way it animates the mind.

Throughout their long evolution as a means of communicating, images have developed their own rhetorics--techniques of composition, style, and content--which increase their ability to move us, or to convey information. (The books of Edward Tufte--Visual Explanations, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, and Envisioning Information--are classics in the study of visual rhetorics, though his focus is largely on the ways images convey information, rather than moving the masses to action.) Clark's text is, finally, a primer of visual rhetorics used in the major political and ideological movements of the 20th. C.

His sub-title--"The Political Image in the Age of Mass Culture"--suggests that when images are used for political purposes and disseminated through mass media, their power to persuade is increased dramatically. His book is thus a lively exploration of how powerful images have been used to motivate masses of people for collective action. Bill Moyers' three-part series, The Public Mind, has a similar theme with a different focus: advertising, newspapers, magazines, television, and film--all those mass media where the power of the image to persuade can be exploited. Moyers suggests that the proliferation of persuasive images can be "all consuming."

Suspicion of the power of images and icons to influence the people has a long historical precedent, including the prohibition of worshipping false images as one of the Ten Commandments, and as a principle of faith in Islam: "Figurative illustrations were not utilized [in ornamental versions of the Qur'an] because Islamic society embraced the principle of aniconism, which is religious opposition to representations of living creatures. This was based on a belief that only God could create life and that mortals should not make figures of living things or create images that might be used as idols. While this principle was strictly unheld in many Muslim areas, such as North Africa and Egypt, pictures were tolerated in some Islamic regions as long as they were restricted to private quarters or palace harems" (Meggs, 53).

Image and Text

The use of images pre-dates all forms of writing, and the power of images to convey information has been used by most cultures on their path towards greater complexity and sophistication. "The early pictographs evolved in two ways: First, they were the beginning of pictorial art--the objects and events of the world were recorded with increasing fidelity and exactitude as the centuries passed; second, they evolved into writing. The images, whether the original pictorial form was retained or not, ultimately became symbols for spoken-language sounds" (Philip Meggs, A History of Graphic Design, 3rd. ed, New York: Wiley and Sons, 1998: 5)

Text is fast, highly-compressed, iconic, robust, stable, and familiar. The alphabet has a long and interesting history which demonstrates the evolution of writing from its origins as pictures of sounds and meanings--hieroglyphs in Epypt and ideograms in China, for example--to the more abstract and flexible phonetic alphabet in use by many contemporary cultures. The following example, and its translation, illustrate the powerful compression of meaning capable of both ideogram and phonetic alphabet:

"Tigers do not breed dogs"________"Calamities do not occur singly"

The nearest equivalent in English to this first proverb is perhaps "Like father, like son." The equivalent phrase for the second example would be "It never rains but it pours." (http://acc6.its.brooklyn.cuny.edu/~phalsall/texts/chinlng2.html) Mao Zedong was particularly adept at incorporating classical features of this kind into his political speeches. The pithy saying or fable is the verbal equivalent of a powerful image and continues to be a staple of political campaign speeches around the world.

It might be argued that there is nothing new about the juxtaposition of text and image: from Medieval illuminated manuscripts to propaganda posters and glossy magazine ads, our culture has developed the combination of text and image to a high art. In many ways, the juxtaposition of text and image signifies a persuasive visual argument: we expect to be prompted towards a belief, a fear, or a desire satisfied.

Archetypes: Images that Disturb and Inspire

The power of images and text often derive from their ability to resonate as archetypes: a recurrent symbol or motif, or, in Jungian terms, an inherited mental image from the collective unconscious. The anthropologists Carl Schuster and Edmund Carpenter believe that indeed there are such images, and they are not necessarily buried in the unconscious. In Patterns That Connect: Social Symbolism in Ancient and Tribal Art, Carpenter argues that similar patterns and motifs in widely-dispersed cultures leave no doubt that visual archetypes exist, and may result from the way memory generates formal patterns in "perpetuating" culture. How are these archetypal images--with a broad base of recognition, even across cultures--used for persuasive purposes?

Making a mental inventory of our own bank of images will help us think through the question of the power of images. Let's try a brief experiment. Try to conjure up at least one image that:

- You can't seem to get out of your mind.

- Terrifies you.

- Inspires you.

- Makes you feel insecure or paranoid.

- Reflects or stimulates your desires.

- Makes you angry.

- Makes you sad or melancholy.

- Inspires patriotism or nationalism.

- Makes you want to do something for society.

- Looks tacky, kitschy, or sentimental.

- Reminds you of the spirit, or divinity.

- Inspires you to be good.

- Personifies evil.

Where do these images come from--experience, the media, dreams, art, advertising? Consider the power these personal images have to affect your emotions and colour your thoughts. Now, imagine that artists, advertisers, propagandists, or politicians--all technicians of the power of images and words--work overtime to communicate with your deepest emotions through powerful images. They appropriate images, icons, archetypes, and cultural codes to move us, sometimes consciously, sometimes from the unconscious. Combining text with these images shifts the technique of persuasion because text engages our analytical reasoning in ways that images can by-pass. Knowing something about the distinctive and overlapping rhetorics of images and text--and paying attention to how these rhetorics have been composed--will help us avoid being motivated unconsciously against our best interests.

Art and Propaganda: Introduction (7-15)

In his Introduction to Art and Propaganda in the Twentieth Century, Toby Clark reviews the origins of the word propaganda--"the systematic propagation of beliefs, values or practices"--from the formation in 1622 of Congretatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith). This missionary organization established by Pope Gregory XV was charged with the responsibility of educating people in the values of the Catholic religion, and an attempt to counteract the rapid growth of Protestantism. The educational emphasis of the word is significant because, in one sense or another, propaganda is about education--whether about religion, politics, or products. Until the early 20th C. the term was largely neutral in connotation.

During WWI, however, British recruitment techniques and demonization of the enemy contributed darker connotations, including censorship, distortion, and misinformation. The massive scale of the war effort--and the attendant psychological warfare--also meant that the persuasive techniques used to mobilize the troops and get the folks back home to support the war effort dominated the media, and sent a strong message to the enemy. The average citizen was bombarded with motivational messages--in the news, on the radio, in posters and billboards--that reflected an unprecedented intrusion of public messages into the private lifeworld.

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm, 1950

Clark next considers the related questions: Can art be value-free? Can propaganda be good art? His example of Abstract Expressionism illustrates how non-figurative art came to signify freedom of expression (only possible in a democracy) in contrast of the socialist realism of Stalin's regime in the USSR. While socialist realism came to be considered kitsch (populist, sentimental, and figurative), Abstract Expressionism was elevated to become an art style more sophisticated, refined, and objective. However, as Clark points out, even a high art form (meaning free of promotion) like Abstract Expressionism could be used in an ideological war against communism. Later in the introduction, Clark makes an important distinction about the context of propaganda and art: "As is the case of Abstract Expressionism, propaganda in art is not always inherent in the image itself, and may not stem from the artist's intentions. Rather, art can become propaganda through its function and site, its framing within public or private spaces and its relationship with a network of other kinds of objects and actions" (13). Does the work of art become propaganda when it is hanging high on the walls of a major bank lobby? He leaves us with the question, Can any art be value-free?

Citing the work of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) and Francisco de Goya (1746-1828), Clark suggests that the use of art for political propaganda--as opposed to religious propaganda--was stimulated by the Romanticism of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Since romanticism "asserted the artist's individualism and social independence" (10), the artist could well be a critic of society (even though, ironically, self-expression was deemed to be above worldly concerns). When David painted the portrait of his murdered friend and fellow revolutionary Marat, he was engaged in propaganda of the highest order.

We might well compare his portrait with one by Attila Richard Lukacs, a gifted Canadian neo-romantic painter now living in Berlin. A survey of Lukacs' work shows a convergence of painterly style and striking social commentary that is reminiscent of David's neoclassic high art propaganda. Lukacs would, no doubt, resist any suggestion that his work is propaganda; in fact, the ironic framing of his subjects suggests that his work is "oppositional" propaganda.

Clark provides interesting examples of art which attempt to subvert totalitarian or repressive regimes--dissident acts that he suggests might be thought of as oppositional or anti-propaganda. I agree with his argument that such distinctions are difficult to sustain--many repressive regimes began as oppositional movements to the status quo. One of the features of propaganda studies is a tendency to point to what your opponents do as propaganda, and what you do is news, education, art, or entertainment. Culture jamming, tattooing, and graffiti are examples of activist art with subversive intentions, often turning commercial art against itself as a critique of consumerism, materialism, or bourgeois values. We have to resist the temptation to think of all mass media as conduits for propaganda of the status-quo. As Clark points out towards the end of his introduction, "[I]mages devised for mass consumption can express the views of a radical subculture" (14).

The Technological Society

In Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes, Jacques Ellul argues that propaganda and the technological society are interdependent. Whatever the variety of propaganda, it is always associated with effectiveness: "Ineffective propaganda is no propaganda" (x). As an instrument of indoctrination arising from the "will to action," propaganda is a technique of social influence that treats society as a machine that can be tuned up, re-engineered, or re-programmed. Ellul argues that the technological imperative--the reliance on technology to provide solutions and progress--corresponds to the rapid growth of propaganda in the 20th C. "Not only is propaganda itself a technique, it is also an indespensible condition for the development of technical progress and the establishment of a technological civilization. And, as with all techniques, propaganda is subject to the law of efficiency" (x).

Clark makes a similar argument when he claims that modern propaganda is "intimately linked with the rise of mass culture" (13). And mass culture is formed through the actions of mass media, capable of broadcasting messages quickly and effectively and thus influencing opinion and attitude across a nation, or even across national borders to a global audience. "Mass-production of images and messages by industrial techniques" (Clark 13) forges the mass audience. Without mass media, the scope of propaganda is limited; without propaganda, the technological imperative is less effective. This entanglement of technological society with the means of mass persuasion seems to be reflected in this image of an elephant from the Aberdeen Bestiary.

References

- Adbusters: Manufacturing Desire

- The Diamond Sutra, The World's Earliest Dated Printed Book

- Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes. New York: Vintage, 1965

- Greek Gospel Illumination

- Lindisfarne Gospels

- Attila Richard Lukacs at the Diane Farris Gallery

- Powers of Persuasion: Poster Art from World War II: from the US National Archive Gallery

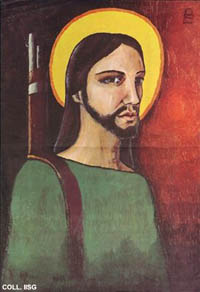

- Alfredo Rostgaard: Christ Guerrilla (1969). International Institute of Social History.

- Edward Tufte

- Carl Schuster and Edmund Carpenter. Patterns That Connect: Social Symbolism in Ancient and Tribal Art. New York: Abrahms, 1996.

- Veneration of Images, The Catholic Encyclopaedia